Flat Qubiters

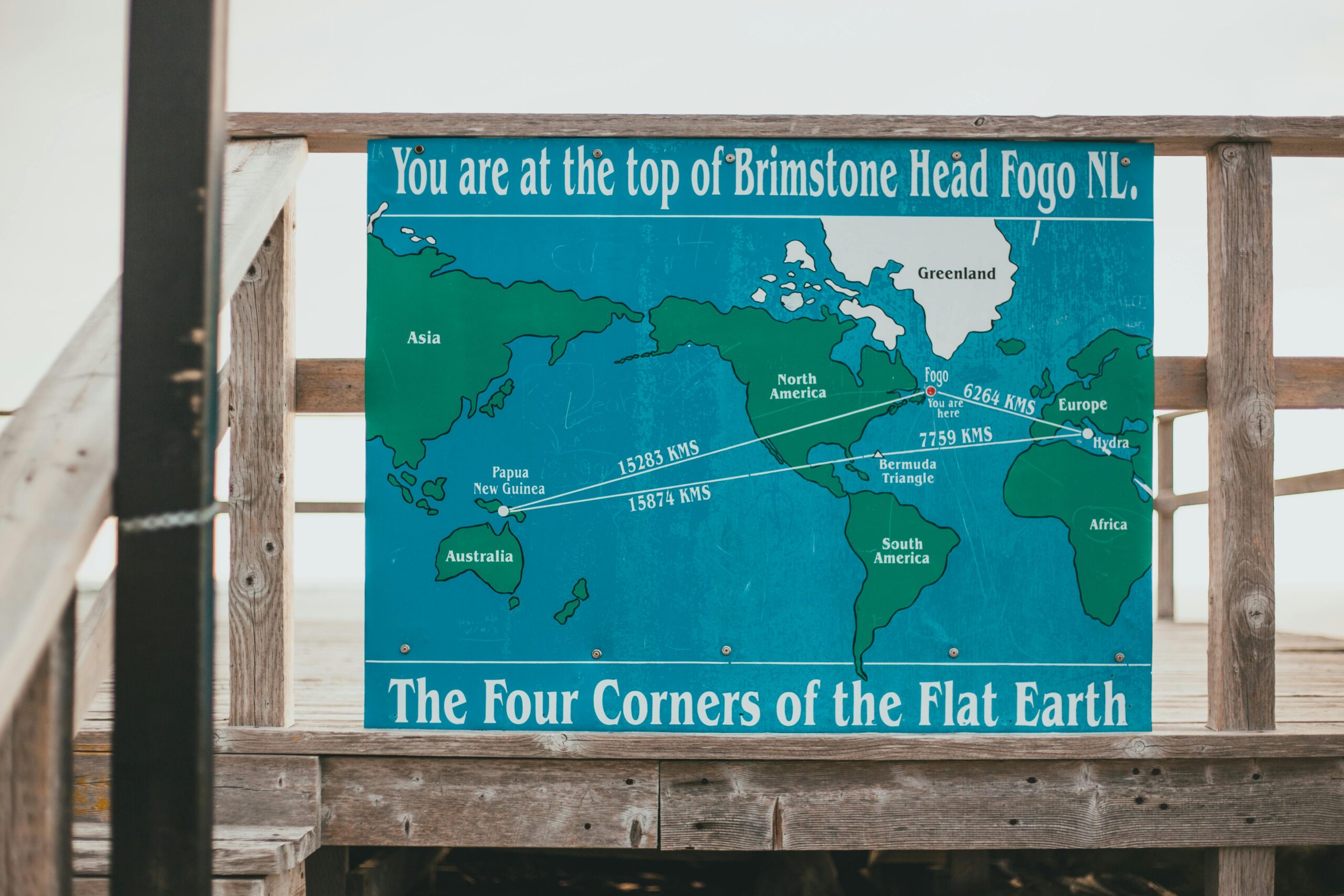

Flat Earthers are a small but growing community of people who, as the name suggests, believe that the Earth is flat. They claim, despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary, that they can account using flat geometry for all the experiments revealing the Earth’s spherical shape. Now forget for the moment all the beautiful logic stretching back to the Ancient Greeks (Eratosthenes comes to mind since he measured the radius of the Earth by exploiting the fact that the same stick casts different shadows in different places on Earth but at the same time); just think about all the images taken from satellites. The Earth looks round and from all possible angles. Yes, but for Flat Earthers, all these images are fake news. They are a conspiracy of (insert your favourite culprit here) for the reasons of (insert your favourite reason why someone would want to lie).

Anyway, I don’t want to get even more sarcastic here. Instead, I’d like to tell you how the shape of all possible states of a quantum bit (affectionately called a qubit) is also a sphere just like our planet! However, just as we have Flat Earthers, there are also people in the quantum community who believe that qubits too are flat. Hence the title. Only, Flat Qubiters is a name I made up for this blog; in reality, the proponents of flat qubits are called Hidden Variable Theorists.

Photo by Erik Mclean: https://www.pexels.com/photo/information-board-on-fogo-island-newfoundland-canada-8266735/

I will expand on the analogy but, first, I need to explain how we know that qubits live on a sphere (called the Bloch Sphere). One way to think about this is to measure the qubit in the z direction, then in the direction very close to z but going towards x. And so on, making measurements along directions close to one another until you’ve reached the x direction. Then you continue the same way towards the y direction. Finally, when you reach the y direction, you go back towards the z direction and you stop when you reach z. This dragging of the quantum state by making many measurements that are very close to one another was suggested by Johnny von Neumann. Some people call it the anti-Zeno effect (I won’t elaborate on why as this deserves a separate blog).

The punchline. You’d expect (and you’d be wrong) that the final state of the qubit after all these measurements is the same as the initial one (since you started with z and ended with z), however, there is an extra phase generated (called the Pancharatnam phase) in front of the state. And this extra phase can be (and has been) detected in quantum interference experiments.

Now the analogy with the Earth. Imagine that you take a stick and start at the North Pole. You point the stick in the direction of your motion and start the journey toward the Equator along a longitude (while also holding the stick in the direction of motion). When you get to the Equator, you don’t twist or turn but continue to walk for a quarter of the Earth’s circumference (along the Equator, the stick now pointing downwards). Then you return to the North Pole along the great circle (the longitude), while again making sure that there are no additional twists or turns. And, to your great surprise, when you come back to the North Pole, the stick now points in the direction perpendicular to how you started!

Assuming for simplicity that the radius of the Earth is of unit length (I can hear Eratosthenes spinning in his grave), the angle through which the stick has turned equals the area that you enclosed on your journey (which is one-eighth of the total area, therefore equal to pi/2, or 90 degrees). And this would never be like this unless the Earth was a sphere. If the Earth was flat, your stick would be pointing in the same direction upon your return!

Mathematically speaking (the specific branch of mathematics being differential geometry) the descriptions of the change of qubit’s state when dragged on its journey and the stick going around the Earth are identical!

The Earth is spherical because of gravity, but what is it that makes the qubit spherical? It’s the fact that its components, the x,y and z values of the qubit, are not ordinary numbers, but are instead what Dirac called q-numbers. The qubits x, y and z components cannot be specified all at the same time. If they could, the qubit space would be flat. And it’s for this reason that I called the believers in Hidden Variables (and Hidden Variables are meant to be ordinary real numbers) Flat Qubiters.

Let me push the analogy a bit further. Here it gets interesting, especially since I’ve never heard anyone make this particular observation before (while what I said above is just a colourful way of talking about the work of Chris Isham, the guy whose influence was crucial in making me a quantum physicist – clearly a possible topic for yet another blog 😊).

I will start with an apparent paradox. If qubits are spheres and everything is made up of them, then how come we see ordinary numbers as outcomes? Why do measurements of “curved” things give us something flat? The reason for this goes back to something that Schrödinger emphasised over and over again. When two qubits get entangled (you could think that each measures the other) then each of them becomes flat (classical) while together they are highly curved (quantum). So, no paradox here after all. Quantum measurements result in flat qubits locally (for each qubit) while maintaining the spherical character globally (i.e., for both qubits together).

Now, believe it or not, the same is true in Einstein’s theory of gravity. Namely, gravity for Einstein was the curved character of space and time. And here we have a similar apparent paradox to the above one. If gravity curves the motions of all objects, how can you measure it in the first place? In other words, both your ruler and the clock are distorted in the same way as the ball whose motion you are trying to track. Looks like you can never measure anything to be curved since everything is curved in exactly the same manner!

But that exactly is the point of General Relativity (just as entanglement is the point of quantum mechanics). It is called the equivalence principle. If you are falling down in Earth’s gravity together with an apple, then both you and the apple are affected in the same way. If you were inside a box, you wouldn’t even know that it’s falling towards the Earth since the apple’s motion would look like no forces are acting on it (because the same force is acting on you at the same time so that the apple is stationary with respect to you). For Einstein, everything in spacetime looks flat locally even though it is curved globally just like for Schrödinger all quantum bits look classical locally while they are highly entangled globally!

Final thought. People keep saying that gravity cannot be quantised because General Relativity is so so different to quantum mechanics. But in this blog, I am suggesting the opposite. Both theories seem to be underpinned by the same underlying logic. Both contain entities that locally look flat (like the Earth from our limited perspective of walking around say a football pitch), but globally these entities are clearly curved (just like the Earth is when viewed from a satellite orbiting around). All this suggests to me that quantising gravity mightn’t be such a Big Deal after all…

Sign up to my substack

BOOKS

ASK ME ANYTHING!

If you'd like to ask me a question or discuss my research then please get in touch.