Quantum Relativistic: Being and Becoming

I’ve always found it curious that, while physics profoundly deepens our understanding of reality, it still does not answer some of the most fundamental questions of philosophy (I guess that’s why these questions belong to what we call “meta”physics).

One of those fundamental questions is whether we should be realists or idealists when it comes to our understanding of the world around us. Is there a world out there independently of us, and we just happen to observe things as they are in it, or is the whole perception of what constitutes the external reality just a figment of our imagination, all just a construct of our brain? Believe it or not, physics is agnostic on this particular issue (in the sense that both views, and everything else in-between, are all tenable).

And there are many more questions of this kind. The particular one I’d like to talk about here is that of “being versus becoming”. This concerns our understanding of time and uncertainty. Is reality composed of one thing after another (as Heraclitus would have it – you cannot step into the same river twice) or has everything that we think of as being in the future actually already happened and exists in some higher dimensional reality (as Parmenides thought – change is simply an illusion)? There are of course all sorts of mixtures of the two extreme positions that everything is becoming and in a continuous state of flux versus all already exists in one big “block” universe. Plato for instance thought that the things we observe are changeable, but this is only because they are poor replicas of what he thought were fixed and immutable forms, the ultimate level of the unchanging reality (so he – kind of – unified Heraclitus and Parmenides and showed that you can have it both ways).

Anyway, what does physics tell us about becoming and being? Quantum physics seems strongly on the side of becoming. Identically prepared experiments will yield different, unpredictable, results. All the information we have about the experiments we are doing is not enough to tell us the outcome. The outcome is genuinely new, not fully conditioned on the past. Even when we have maximal information, new information always arises from observations. This is Heraclitean more than anything Heraclitus ever said: you really can never step into the same quantum experiment twice.

But, our other current best explanation of physical reality, general relativity, seems to support Parmenides. The reason for this is as follows. For any event you can think of in this universe of ours, such as a click of a photodetector in some experiment, there is an observer for whom this event lies in their own past. But that means that they already know its outcome! So even if the detector clicking or not clicking lies in my future, and the outcome is completely random and therefore not known (not even knowable) to me, there is some other observer in the universe for whom this event has already happened (and they know that the detector has registered a click).

Einstein tried to console his best friend’s wife using relativity, by saying that even though his best friend had just died, we are actually all dead with respect to some, suitably chosen, observer (you can judge for yourself how well this worked as a consolation, but Einstein’s phrase that remained is “the passage of time is an illusion, albeit a persistent one” – Parmenidean for sure).

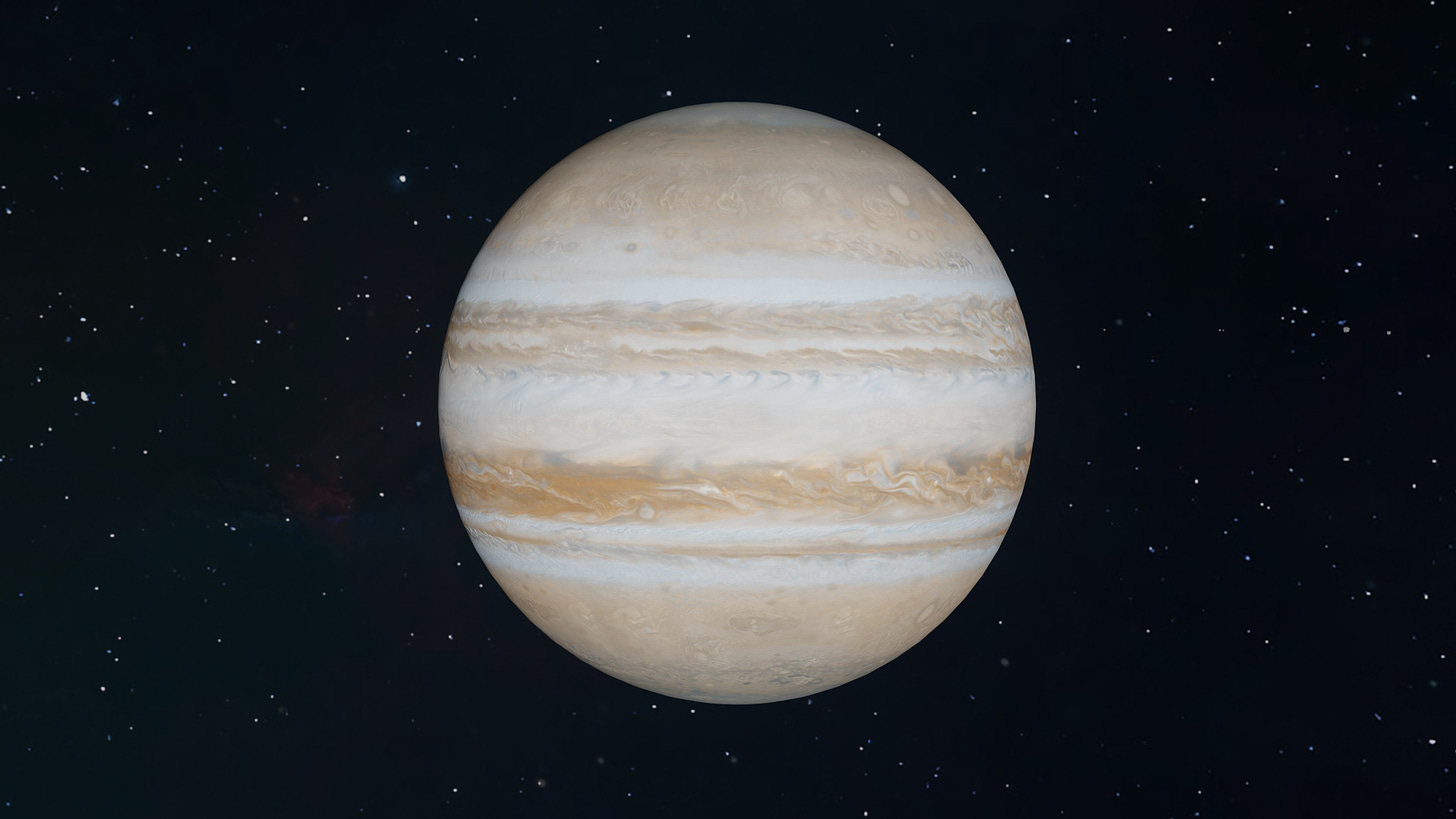

Let me give you a mind-blowing example of this (all I am doing is upgrading Einstein’s train thought experiment to make it quantum). Suppose you are standing still looking at Jupiter (probably the brightest “star” you can see these days at night if you are geographically close to me). And, suppose further, that there is someone on Jupiter sending a photon through a beam splitter in their own laboratory and observing which way it comes out. Now, if the guy on Jupiter has just fired the photon, and this photon has not yet gone through the beam splitter, then which way the photon goes, lies in the future for him as well as for you. The outcome is not known to either of you at that point (because things are simultaneous for both of you).

However (and this is the mind-blowing bit) for a passer-by, whose position is the same as yours, but happens to be moving away from Jupiter, this event lies in her past! As far as she is concerned, the photon has not only been fired, but has entered and exited the beam splitter and has already been detected in one of the two detectors.

You’ve gotta be kidding me, I hear you say. How can this be? It can be (logically speaking, see below) and it is (factually speaking, see below). This is the main message of relativity, namely that simultaneity is relative.

What I think of as things happening at the same time for me (I am in the bath and my phone in the living room rings) someone else might see differently. There are observers for whom the phone rings before I enter the bath, in which case they are thinking “why on earth did he just not answer it?”, and there are observers who see it the other way round, in which case – please feel free to make up your own joke at this point.

Ok. But doesn’t this contradict the quantum randomness? I mean, how can anything be random if there is always an observer who already knows the outcome? (I don’t mean God, I simply mean someone moving in a certain way with respect to you).

I’m going to make a pause here just to say that this is why I love physics. Just look at the tightrope we have to walk to try to reconcile seemingly contradictory aspects of nature arising from our different theories and experiments.

But, reconcile we can. And it’s all to do with the fact that while there is no absolute past, present and future in relativity, there is no such thing in quantum physics either! This might come as a surprise to some of you, but it ought not to if you’ve read some of my past blogs 😊. In quantum physics, even the unobserved events can affect the future events. Past, in the sense of what has definitely happened, is also relative in quantum physics, relative to observers (which are nothing special – just other physical systems).

I’d like to go back to the Jupiter example to spell out what I have in mind here. What it means for the person on Jupiter to observe which detector clicks (or what it means for anyone for that matter) is that he becomes entangled to the state of the detectors. It’s this entanglement that ultimately allows us to reconcile quantum physics and relativity. In that entangled state, which has two branches, in one branch he has observed one detector click, while in the other he has observed the other detector click – and both branches exist in a superposition. In each branch, the observer in that branch sees a definitive event (one of the two detectors has clicked). But, as far as another observer is concerned both still exist in an entangled state (like Schrödinger’s cat).

This way, the “still” observer on earth, is simultaneous with the state of the photon before it entered a superposed state (at the output of the beam splitter), but the moving observer, is simultaneous with the entangled Schrödinger’s cat-like state. And that’s perfectly fine, there is no contradiction here (countless people have tried to find a contradiction, but – as you can see from the argument above – there just ain’t one anywhere in sight).

Therefore, a potential conflict between the randomness of becoming and the determinism of being is solved through quantum entanglement as far as quantum physics and relativity are concerned.

This is why the current best theory we have – quantum field theory, which successfully combines quantum physics and relativity, does not settle the question of being versus becoming. Both views are still possible. In relativity, locally (to an observer) things are becoming (even though another observer can see them as already being!). In quantum mechanics, we can have a perfectly static picture of an enormous entangled state in which all things have already happened, while in each branch they “look” to the relevant observers as becoming. And, Bob’s your uncle.

Finally, for something completely different. Whenever a physicist comes across a question that leads to views which cannot be resolved within physics, they are tempted to think that the question itself might be wrong, or vacuous or ill-posed or all of the above. Philosophers, after all, do talk about things that are frequently non-sensical, so no surprises there.

But, and this is a wild speculation in its own right, maybe the question isn’t whether reality is really out there or not, or whether things happen or just exist. It might just be that the key question instead actually is: what is nature trying to tell us by allowing us to have (seemingly infinitely) many consistent philosophies of reality that all comply with our scientific knowledge? Clearly, no one on Earth has any idea, though there might be some observers out there who already know the answer even to this question.

Sign up to my substack

BOOKS

ASK ME ANYTHING!

If you'd like to ask me a question or discuss my research then please get in touch.